http://time.com/4417809/esperanto-history-invention/

The Serious History Behind

Esperanto

July 26, 2016

Image Esperanto creator L.L. Zamenhof.

Olivia B.Waxman -

July 26, 2016

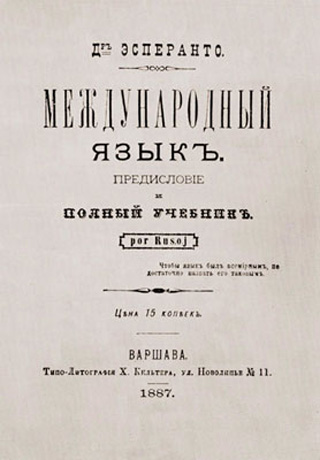

The first Esperanto textbook was published on July 26, 1887,

by its inventor L.L. Zamenhof.

Over 1,000

speakers of Esperanto have been expected to gather this week at the 101st World Esperanto Congress in Slovakia to celebrate

Tuesday as the 129th anniversary of the “birth” of the language, as July 26,

1887, marked the publication of the first Esperanto textbook by L.L. Zamenhof.

The Polish doctor created the language, which is essentially a set of roots

that can be turned into words with

certain endings that create different parts of speech.

Though

Esperanto can be seen as something of a punchline today, its

origins can be found in serious world-historical matters.

Zamenhof

identified the need for a “neutral tongue,” as TIME once called it, while growing

up in Bialystok in northeastern Poland, home of a mostly Jewish population and

a few main ethnic groups that were not communicating. Humphrey Tonkin, the

former president of the University of Hartford and the Universal Esperanto

Association who currently represents the latter at the United Nations, explains

that while Zamenhof was in medical school in Moscow in his 20s, his world

changed: “The czar gets assassinated, Jews are accused of carrying out the

assassinations, and there’s a whole round of pogroms in Russia that eventually

spread westward into Poland.”

The wave of

anti-Semitism underscored Zamenhof’s thinking that the world needed a single

language that would make it possible for people to bridge gaps of religion or

ethnicity. Meanwhile, technological developments like the telegraph meant that

people from vastly different backgrounds were suddenly in closer contact than

ever. “It’s also a period when the first international organizations get

created, like the Universal Postal Union and Universal Telegraphic Union,”

Tonkin says. “[It was] an earlier wave of globalism that destroyed with the

rise of nationalism in the beginning of the 20th century.”

Considering

that context, the language’s structure was strategic. Even though a

Yiddish-based grammar would have been a natural choice for appealing to the

Eastern European Jews who had inspired him, Zamenhof based his new tongue on

the Romance languages. “He picked a language structured like Latin because

Latin had prestige and Yiddish had none,” Tonkin says. The name Esperanto —

meaning “one who hopes” — comes from the pseudonym under which the Jewish

doctor published the textbook during a period of severe censorship of Jews in

the Russian empire, but also because (in a soap-operatic twist) “he couldn’t

use his own name because his father was one of the censors who censored Hebrew

and Yiddish works.”

Esperanto

wasn’t the first invented language of its time. A German Catholic priest tried

to make “Volapük” catch on seven years earlier, but it died out because, “he

didn’t want anyone else to make decisions about it,” says Arika Okrent,

linguist and author of In the Land of Invented Languages. “Zamenhof just

said, ‘Here it is,’ and he didn’t meddle with what people started doing with

it.'”

Partly

because Zamenhof let the language grow naturally, Esperanto is now said to be

spoken in over 120 countries, boasts a Wikipedia site with more than 230,000

articles and has 465,000 signups on language-learning app Duolingo.

But

Esperanto also had another reason to succeed: though other invented languages

of the era were designed for practical purposes—to further scientific

collaboration or assist with trade, for example—its pie-in-the-sky aims had immediate

and broad appeal. And, Okrent says, that appeal has endured even as Esperanto

has failed to become a widely spoken, everyday language.

“Esperanto

people were drawn to this vision of world harmony,” she says. “The ideals kept

it going through subsequent decades where it became clear that it wasn’t going

to work in the way most people thought it would.”//-

JAM EN LA JARO 1923

TIME MAGAZINE INFORMIS PRI ESPERANTO

THE

LEAGUE OF NATIONS: Esperanto Spurned

Monday, Aug. 13, 1923

http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,727293,00.html

"The movement to make Esperanto a world language for auxiliary

international purposes received a rebuff from the Commission of International

Coöperation, which had been invited to express its opinion on the question by

the Assembly of the League of Nations.

The

Commission decided to eschew synthetic languages, and to invite the League to

favor the selection of a living language as one of the most powerful means for

bringing the nations of the world together. English and French must fight it

out.

Even

Esperanto can be tinged with politics...".